Difference between revisions of "MABunkerHillMonument"

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

</p> | </p> | ||

| − | ==== GENERAL JOSEPH WARREN AND BUNKER HILL ==== | + | ==== GENERAL JOSEPH WARREN AND BUNKER HILL, 1872 ==== |

''From Moore's Freemason's Monthly, Vol. XXXI, No. 10, August 1872, Page 307:'' | ''From Moore's Freemason's Monthly, Vol. XXXI, No. 10, August 1872, Page 307:'' | ||

| Line 179: | Line 179: | ||

General Joseph Warren was born in Roxbury. Massachusetts, June 11th, 1741, graduated at Harvard College 1759, and after teaching school in Roxbury for a few years commenced the practice of medicine. | General Joseph Warren was born in Roxbury. Massachusetts, June 11th, 1741, graduated at Harvard College 1759, and after teaching school in Roxbury for a few years commenced the practice of medicine. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==== NEW ENGLAND CRAFTSMAN, 1925 ==== | ||

| + | |||

| + | ''From New England Craftsman, Vol. XX, No. 9, June 1925, Page 293:'' | ||

| + | |||

| + | h'''BATTLE OF BUNKER HILL''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | ttp://masonicgenealogy.com/MediaWiki/images/FrederickHamilton1925.jpg<br> | ||

| + | ''Rt. Wor. [http://masonicgenealogy.com/MediaWiki/index.php?title=MAGLFHamilton Frederick W. Hamilton], Grand Secretary, Grand Lodge of Massachusetts''<br> | ||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | ''(Copyright 1925, by The Masonic Service Association of tlie United States. Reprinted by permission.)'' | ||

| + | |||

| + | The 17th of June, 1775, was one of those bright, quiet days which show the New England climate at very best. At daybreak the sleeping inhabitants of Boston and the neighboring towns were aroused by the continuous thundering of heavy guns from the upper harbor. Evidently something unusual even in those stirring times was happening. This is what it was. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Ever since the first British regiments had been sent to overawe the town of Boston some eight years before, the garrison had been increased from time to time until the British forces numbered about 10,000 men. General Gage was in command, and with him were Howe, Clinton, and Burgoyne, all familiar names in the story of the next eight years. A few weeks before, on the 19th of April, a British detachment had attempted to destroy the ammunition and supplies which the Americans had gathered at Concord. The story of what happened that day need not he retold here. Its effect, however, was of the utmost importance. The resistance of the Colonists had been solidified and strengthened. The New England militia had gathered in large numbers around Boston, and their forces were constantly increasing. Their organization, however, was crude and imperfect. Washington had been appointed to take command of the Colonial troops, but had not yet reached the neighborhood of Boston. The troops surrounding Boston were under command of General Artemus Ward. General Ward was a man of the highest character and warmest patriotism but advanced in years and of moderate military ability. From his headquarters in Cambridge he was directing the operations which amounted practically to a siege. The Americans were in sufficient force and sufficiently well posted to hold the British closely confined to the city. It was unsafe for small parties of British to venture out, and General Gage did not care to precipitate hostilities by movements in force. Each side was watching the other warily: the Americans anticipating an attempt to break out and the British fearing movements which might make their position untenable. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Under these circumstances General Ward, on June 16, sent out a working party of about 1,200 men under Colonel William Prescott to fortify Breed's Hill, in Charlestown. It does not appear to have been General Ward's intention to bring on an engagement. He appears to have had in mind only the erection of fortifications which would block an attempt of the British to gain the open country by way of the pear-shaped peninsula of Charlestown neck behind it, an exit from the city which was not fortified. Arriving on the ground, however, Prescott went beyond Breed's Hill and fortified Bunker Hill, apparently forgetting the defensive nature of the movement ordered by Ward and considering that guns mounted on Breed's Hill would be able from that point to inflict much more damage on the British in Boston and their ships in the upper harbor. This was quite true, and was the deciding element, as we shall see, in bringing on the judgment. The position, however, was much more exposed and much less easily defensible than Bunker Hill. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The first troops were accompanied by Colonel [http://masonicgenealogy.com/MediaWiki/index.php?title=MAGLRGridley Richard Gridley], who had commanded an artillery regiment in the French wars, and had considerable training as a military engineer; almost, if not quite, the only engineer officer then in the Colonial Service. Gridley commanded the artillery and laid out the fortifications. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p align=center> | ||

| + | http://masonicgenealogy.com/MediaWiki/images/Trumbull_BunkerHill.jpg<br> | ||

| + | ''Battle of Bunker Hill,''<br> | ||

| + | ''From Painting by John Trumbull'' | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | At daybreak the Americans and their growing fortifications were seen from the British ships, which immediate1y opened fire, though with very little effect. The sound of the guns, and the news of what it signified, aroused Gage, who consulted witli his generals as to what should be done. Their decision was a very expensive blunder. It was agreed that heavy batteries on Breed's Hill would compel the evacuation of the city, exactly as it was compelled nine months later by Washington's hatteries on Dorchester Heights. There was no question that the Americans must be cleared out of that position. The position itself was a trap. The British had control of the water, and could move their troops upon it at will. Charlestown neck was narrow and could be swept by the fire of the English warships. Protected by this fire, it would have been perfectly possible to land a force which would have cut off the Americans and compelled the surrender of the entire force. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Gage was a British General of the old school, of the highest personal courage, but as arrogant and obstinate as he was brave. Concord and Lexington had taught him nothing. He did not believe that the New England militia, even behind breastworks, would stand for a moment before British regulars. He scorned to employ the obvious tactics which he would have used against an ordinary army. He probably felt that the moral effect of marching over the Americans' breastworks and sending their ill-trained defenders scuttling to the rear would be far greater than could be accomplished by scientific military manoeuver. Accordingly, at ten o'clock in the morning he issued a general order directing certain troops to assemble and march to the waterfront to be ferried across to Charlestown. The order is so drawn that it is impossible to tell at this time just what commands were indicated, or even their approximate strength. It is probable, however, that the total British force engaged, including reinforcements which were later sent over, was about 3,000 men, although some of the people of Boston reckoned it as high as 5,000. No official figures of the force engaged were ever published by the English. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The troops assembled as directed and paraded in a body through the streets of Boston. It was evidently Gage's intention to hold the ground occupied. It is an interesting side light on the military customs of the time to know that, although these men were sent out to fight, and would be separated from their base of supplies by a distance which could be traversed in two hours at the outside, they were sent out in full dress uniforms, and provided with heavy marching equipment and three days' rations. All this in the middle of a warm summer day. Such disregard of ordinary consideration for the comfort and effectiveness of soldiers on duty was characteristic of the English Army at this period, and long after. Knglish soldiers faced Hie climate of India in European uniforms and bearskin hats, while Lord Wolseley tells us that so late as 1853 he had to go into action in the steaming jungles of Burma in a close-fitting scarlet tunic with a high, tight collar. | ||

| + | |||

| + | At twelve o'clock the crossing to Charlestown began, and at three o'clock the British lines were formed for the assault and moved toward the breastworks. The British advance must have been a very beautiful spectacle. Their scarlet-clad lines moved forward with the regularity of the parade-ground, the sun reflecting in myriad points of light from the polished metal of their equipment and the rows of glittering bayonets. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Behind the American breastworks the militiamen were out of sight. Only Colonel Prescott, an experienced veteran of the French wars, walked coolly back and forth on the top of the breastworks, keeping his inexperienced and somewhat nervous men in order. The Americans had been ordered to hold their fire until the British had almost reached the breastworks and, with the exception of a few scattering shots from the nervous and impatient, the order was obeyed. When Prescott considered that the right time had come, he gave the order and a blast of fire destroyed the front ranks of the British. The first volley was followed by a rapid and continuous discharge before which in a few minutes the British broke and fled back to the shore. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In a few moments, however, discipline asserted itself, the officers reformed their men, and a second advance was made. In the meantime the town of Charlcstown had been set on fire by the British and the second assault was partly screened by clouds of smoke from the burning buildings. Again the Americans waited until the British were almost upon them, again the assailants were blasted away by the rifle fire of the defenders. British officers who had served at Fontenoy and other pitched battles on the Continent declared they had never experienced anything like it. A second time the British retreated. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Gage held a hurried consultation with his officers. The gravity of the situation was fully recognized, but British pride was not yet ready to admit defeat, and the possibility of being turned out of Boston by heavy guns which might be mounted in the American works, was again urged. Contrary to all teachings of military prudence, Gage ordered a third assault, which was delivered at five-o'clock. With extraordinary courage and tenacity the British returned to their apparently hopeless task. This time, however, the fire which received them was much less severe. They succeeded in placing some guns in position to rake the American works. The ammunition of the Americans was exhausted. Without bayonets, they had only stones and clubbed rifles with which to resist the British. Even so, they made a desperate resistance, and it was not until their defences were actually in British hands that they broke and streamed away over Charlestown neck, leaving the British in possession of the hill. It was in this last phase of the engagement that the greater part of the American losses were sustained. Among the killed and wounded at this point were Warren and Gridley and many other well-known American officers. | ||

| + | |||

| + | It is more difficult to estimate the number of Americans engaged than it is to estimate their opponents. Americans were coming and going all day, but it doubtful if more than 1,500 were actually engaged at any one time. General Gage admitted a loss of 1,054 killed and wounded. It is highly probable, however, that his loss considerably exceeded that number. General Ward's Orderly Book shows an American loss of 450, which probably substantially accurate. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In all probability the defeat of the Americans and their flight from the trap in which they had incautiously placed themselves saved them from much greater loss in the immediate future. Gage had put forth only a small part of his strength. If defeated, he would undoubtedly have renewed his attempt in a more scientific manner, and must eventually have destroyed or captured the entire American force in Charlestown. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The consequences of the battle were far-reaching. When Washington heard of it his first question was whether the Colonists stood their ground, and when informed that they did he expressed confidence in the outcome of the conflict. The British learned to have wholesome respect for the Americans, and recognized the fact that they had a war on their hands, and not a riot. The Americans throughout the Colonies were enraged at the bloodshed of this dreadful day. They too realized that they had a real war on hand and not an armed protest. After Bunker Hill it became increasingly clear that it was useless to hope any longer for an accommodation with the British Government, and that the issue of independence or complete subjugation was clearly drawn. Up to Bunker Hill most Americans still hoped to secure their rights under the British flag. After Bunker Hill that hope faded to nothingness. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Considering this momentous event, it is in the highest degree important that we of one hundred and fifty years later should remember exactly what it was for which the Americans fought. The animating spirit of the Revolution was not the assertion of nationality or a desire to be independent for independence's sake. Up to the day of Bunker Hill, and beyond it, that great majority of the American Colonists who were of English blood were, in heart and in mind, thoroughly devoted to England. They were nationalists to the core, but their nationalism was English nationalism. Their most cherished spiritual and intellectual possession was that heritage of rights and liberties and political ideals, traditions, and aspirations which had developed through the centuries on English soil and under the English flag. These had been flouted and invaded, not by the English people, but by the English Government. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The English Government had fallen into the hands of a race of petty German sovereigns. On the death of Queen Anne the Crown had passed to George, the Elector of Hanover, known as George I of England, who was succeeded in direct descent bv George II, and George III. who was King at the time of which I write. George I and George II were thoroughly German. George III — "Farmer George," as he liked to be called — prided himself on being an English gentleman. It is true that he was born in England, but all his inheritance, instincts, and traditions were German. The Hanoverian kings were never English in heart. Their political inheritance was German absolutism. They were impatient of English ideas, ignorant of English traditions, and unsympathetic witli English ideals. George III did indeed govern England through the ordinary machinery of the two Houses of Parliament and a Ministry, but at this time he dominated Parliament in both Houses through a group known as "The King's Friends." rhrough this domination of Parliament he was doing his best to substitute Ger-uan absolutism for English freedom. The treatment accorded the Colonies by the King and his Ministers was a part of this general plan. The age-long liberties of :he English people were in danger wher-sver the English flag flew, and it was for :hese liberties that the Americans took up arms. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The Americans had no means of breaking this un-English control of the government except by throwing off their allegiance to the mother country. The ordinary methods of political opposition or if resistance at the polls were not open to them. They were placed in the curious attitude of making war against the English Government in order to preserve or themselves the English political system. The success of the struggle for independence was the death blow of the personal government of the Hanoverian kings. Shortly after the end of the Revolutionary War, another revolution took place in England itself. This revolution is often overlooked because in its course not a shot was fired nor a life lost, but when it was over the principles of English liberty were reassured. "The King's Friends" had ceased to be a political power, and the way was clear for the development of the English Constitution and the government organized under if along its traditional lines. The Battle of Bunker Hill was as significant in the history of the English people as it was in the history of the Americans. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p align=center> | ||

| + | http://masonicgenealogy.com/MediaWiki/images/JosephWarrenStatue.jpg<br> | ||

| + | ''Statue of Warren on Bunker Hill'' | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | The Battle of Bunker Hill, considered as the crucial incident in this great struggle, has a particular interest to Freemasonry. Its most obvious interest lies in the participation in it of prominent members of the Fraternity and the tragic death of the most conspicuous of them. Joseph Warren was Provincial Grand Master for North America under a Warrant from the Grand Master of Scotland. In that capacity he had shown the zeal and powers of leadership which distinguished him in other fields. He had been Provincial Grand Master only since 1769, but in that period had shown intense activity, and had not only greatly increased the number of Lodges under his charge, but had impressed them deeply with the vigor of his wise personality, and the earnestness of his Masonic convictions. As a citizen he had early identified himself with the patriotic party. Wise in counsel and energetic in action, he had taken a high position in that goup of leaders who will never be forgotten so long as American history is read. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p align=center> | ||

| + | http://masonicgenealogy.com/MediaWiki/images/JosephWarrenVolunteering.jpg<br> | ||

| + | ''Joseph Warren Volunteering His Services to Gen. Israel Putnam''<br> | ||

| + | ''Before the Battle of Bunker Hill'' | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | He had been chosen President of the Massachusetts Congress, as the Legislature was then called, and held a commission as Major General. Unfortunately for the cause which was so dear to him, his ardent temperament and ear-Best desire to be of personal use led him to forget the great responsibilities of the two positions which he held. He did not stop to think that a life charged with such important duties and responsibilities was too valuable to his country to be risked on the battle-field. Waiving his rank, he rode to the battle-field and offered his services to Putnam, who shared the command with Prcscott, and asked to be put where he could be of the greatest use. He fought bravely in the ranks, and did his best to help the retreating troops get away with as little harm as possible, but was killed in the very last moments of the fight. Undoubtedly the death of so distinguished a leader and the example of his personal heroism was of immense influence at the time, and has made a lasting appeal to the patriotism and to the courage of generations. And yet one cannot help wishing that abilities and character so transcendant might have been spared for the service of his country. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Colonel Gridley, the engineer and artillery officer, who was wounded in the fight, was District Grand Master of the other Provincial Grand Lodge which was operating under the Warrant issued by the Grand Master of England in 1733. Putnam, who commanded the Connecticut contingent, and John Stark, who commanded the New Hampshire men, were both active and well-known members of the Fraternity. Others there were who shared their affiliations, but the time possible for the preparation of this article has not permitted the interesting task of tracing out these personal details. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Behind the personalities of the Masons who took a leading part on this historic day lie the principles of Freemasonry which inspired these men and many others to take the position they did when the great issues of the time were defined. We must remember, what we sometimes forget, that modern Freemasonry is distinctly an | ||

| + | English institution. While ancient Freemasonry struck its roots far into a remote past and distant lands, the direct connection with these ancient Craftsmen and their thought and work can be traced only in England and Scotland. It was there that the Grand Lodges of our modern type were formed. It was there and in the preceding generations that Operative Masonry became slowly developed into Speculative Masonry. It was from there that Masonry spread to the English Colonies, and also to the Continent of Europe. Masonry, in other words, has grown up on English soil and in the English soul. Its fundamental principles of reverence for the Grand Architect of the Universe, truth, honor, and fair dealing between men, broad tolerance of individual opinion, and equality before the law, were at the same time the fundamentals of the best English political and social thinking. The best in English life expressed itself in Freemasonry, and nowhere outside of England could Freemasonry have found scope and support for its development. When Freemasonry came to America it made its appeal to the best hearts and minds in the community. Here, as elsewhere, the Masons, being a carefully selected and self-perpetuating group, were in advance of the development of the mass of their fellow-citizens. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Freemasonry, as an organization, was true to its immemorial principles of barring from the lodge-room all discussions of religion or politics, and refraining absolutely from any participation as an organization in any political movements. Whig and Tory sat side by side in Masonic Lodges. Boston patriots and soldiers from the English regiments quartered in Boston joined under the Charter of [http://masonicgenealogy.com/MediaWiki/index.php?title=StAndrew Saint Andrew's] Lodge to form Saint Andrew's Royal Arch Chapter. Freemasonry did not desert its purpose of furnishing a common ground upon which honest men of all shades of opinion might meet on terms of mutual respect. | ||

| + | |||

| + | But Freemasons inevitably assumed positions of leadership on the side of the liberty of the citizen and the freedom of the individual. The same considerations which carried leading Freemasons of that day into the forefront of public life send the same call of duty to the Freemasons of today. The same devotion to high principle which made these men leaders and impressed their thought and personality so deeply on the history of that time will produce the same results today. It is not the cry of an alarmist to say that, our institutions are in danger. All good institutions are always in danger. The forces of selfishness, greed, ambition, treachery, ignorance, and superstition are part of human nature; they always have threatened the progress of the human race, and they alwav-s will threaten it in any future of which we need to take account. The same clear-sighted courage and indomitable energy which saved the day one hundred and fifty years ago are called for today. The present writer believes that the call will not fall on deaf ears, and that once again, as so many times in the past, the forces of righteousness will conquer. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p align=center> | ||

| + | http://masonicgenealogy.com/MediaWiki/images/Howe_Commissioners1776.jpg<br> | ||

| + | ''Lord Howe and the American Commissioners''<br> | ||

| + | ''In Conference, 1776'' | ||

| + | </p> | ||

==== NEW ENGLAND CRAFTSMAN, 1932 ==== | ==== NEW ENGLAND CRAFTSMAN, 1932 ==== | ||

Revision as of 01:10, 21 December 2015

Bunker Hill Monument

Contents

GENERAL JOSEPH WARREN AND BUNKER HILL, 1872

From Moore's Freemason's Monthly, Vol. XXXI, No. 10, August 1872, Page 307:

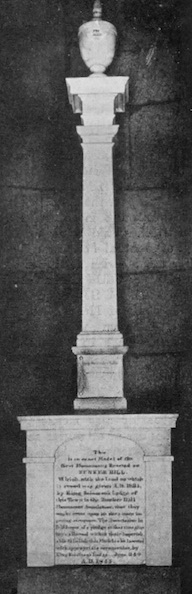

Anything connected with the history of General Warren must be of interest to the American Freemason. The following lines which we find in our scrap-book, were written some fifty-four years ago, after a visit to what was called Breed's Hill. In the remains of the old redoubt stood a monument composed of a brick pedestal, from which arose a wooden shaft of pine surmounted by a Masonic urn. Inserted in the four sides of the column were large slate stones, inscribed with dates of Revolutionary events. One of them contained the following words:

Erected by King Solomon's Lodge,

To the Memory of

Major General Joseph Warren,

Their Most Worshipful Grand Master.

It also contained an extract from one of his popular addresses; "The voice of your fathers' blood cries from the ground: My sons, scorn to be slaves," &c. The stones are deposited in the present Bunker Hill Monument. In 1818, many poplar trees stood near the place:

Why rears yon Urn its lonely head,

Where sweeps the summer's gentle breeze,

Above yon hillock's turfy bed,

In plaintive murmurs through the trees?

Or, why with quiet, pensive tread,

Will thoughtful strangers, drawing near,

The mould'ring slate stone pause to read

Of him who rests in silence there.

'Tis the blest spot where Valor sleeps,

Shaded by wreaths of laurel won —

Where Freedom's guardian Genius keeps

True vigils o'er her gallant son.

Here, once, as at Thermopylae,

The battle shouts of Freedom rose;

Firm as their mountains, and as free,

They nobly braved their country's foes.

No tyrant's purchased slaves were they —

The vassals of no feudal lord;

Their country's call they did obey,

And freedom blessed their righteous sword.

Fair rose the morn on that array

Where bright in arms their foemen stood;

A sadder sight — the close of day

Beheld that sun go down in blood.

The roar of arms to despot's power

And pride, the fun'ral knell has peal'd:

The blood that flowed that fated hour,

Has freedom's sacred charter sealed.

Long, long, these deeds of spotless fame

Shall swell their country's noblest rhyme;

The ray that gilds her heroes' name,

Gain lustre in the march of time.

Soft be the turf where fall the brave;

Peaceful their sleep — their battle o'er —

Above their tranquil, grass-grown grave,

Shall war's dread voice be heard no more.

And oft the stranger passing by,

Shall view with honest pride the tomb

Where patriot's sacred relics lie,

And glory's greenest myrtles bloom.

- P. G. Tisdall.

THE MONUMENT TO JOSEPH WARREN, 1919

From New England Craftsman, Vol. XIV, No. 10, July 1919, Page 313:

A Fitting Masonic Tribute

A little way out from the "Athens of America" is seen the great shaft that marks the spot where was fought the first real battle on American soil for what that great Mason, Thomas Paine, called "the rights of man." A ship entering the port of Boston may see this from many miles at sea. Here fell a young physician but forty years of age that posterity might forever have republican government and free schools from the despotic hands of the sectarian bigot or the political tyrant.

Christ church, on old Salem Street, and Faneuil Hall in Boston tell the glories of Major-General Joseph Warren.

The fathers of the American Revolution were Masons, Samuel Adams, James Otis, Patrick Henry, Peter Faneuil, John Hancock, Alexander Hamilton, Thomas Jefferson, Robert Treat Paine, Matthew Thornton, Seth Warren, Thomas Paine and John Paul Jones are but a few of the many leaders of the great conflict of human liberty since the Sermon on the Mount who were of the world's most democratic institutions. There were ten Masonic lodges in the Continental Army under General George Washington during the eight years of the war—1775-1783. Without the battle of Breed's Hill (commonly called Bunker Hill), with an insane king on the British throne, George III, Thomas Paine and George Washington, there would have been no war with Great Britain. New England has its Bunker Hill Day June 17, but all America has "Flag Day" June 14.

In the thirteen American colonies at that time, the leading men in all walks of life were Masons. So as it is ordained of Infinite Wisdom that the tiny acorn should precede the mighty oak and the little brook the great river, that Wisdom was no less manifest in humble birth of our American Freemasonry in the good colonial days, a brotherhood where the twentieth century creed-monger and the race despot find no solace or haven of rest. In the dying days of the colonial period, when kingcraft threatened the thirteen (American) colonies, Boston' and vicinity took on "new life." There were three Boston lodges whose membership consisted of "ye best blood of ye colony"—St. John's Lodge, the Lodge of St. Andrew, and the Massachusetts Lodge. These lodges were well represented at the "Boston Tea Party" of December 16, 1773. They cere also represented at the battles of Concord Bridge, Lexington Green, ind at Bunker Hill. It is to be remembered that it was in Puritan and Pil-rim New England, Newport, R. I., where was established the first Masonic lodge on this continent, and in Boston, nearly a century later, in L720, that there was a lodge working under the law of "Ancient Usage." These two lodges died from the "wreck of time," but still Boston kept a firm grasp on Masonry. The fight on Breed's Hill at Charlestown, Mass. (historically known as Bunker Hill) which took place June 17, 1775, not only fully opened the great war of the American Revolution, but placed in the New World Freemasonry in a category unique in the history of man.

General Israel Putnam, senior officer in command in this celebrate^ battle, had been made a Mason in 1758 in "Crown Point Lodge," when a soldier under the crown. General Joseph Warren, a young Boston physician, was a Past Master of the Lodge of St. Andrew, Boston, and "Grand Master of North America," as commissioned by the Grand Lodge of Scotland. He fell in the battle in the afternoon and was buried in that trench. He was succeeded in command by Colonel William Prescott (whom the writer is proud to own as his great-great-great-uncle), of an old New England family.

Colonel Prescott had been made a Mason in the "Crown Point Lodge" in company with his brother-in-law, Colonel John Hale, M. D. (the writer's great-great-great-grandfather). The British held Boston till the following March 17. After they had sailed from the port, Dr. John Warren, of Harvard University, a brother of the lamented general, took Warren's body from the trench. It was badly decomposed, but was known by a gold tooth and his late wife's wedding ring on his left hand. Dr. John Warren was also a member of one of the well-known old Boston lodges. The wedding ring is now owned by Miss Elizabeth Warren Waldron, of Somerville, Mass., a member of the Order of the Eastern Star in Boston. There were many Masons engaged in the battle, including Colonel John Stark, Captain Henry Dearborn, Colonel Thomas Crafts, General Alexander Scamsell, Captain Michael McClary, and Captain John Brooks. James Otis was in the engagement as a private soldier. Eight well-known Charlestown residents were Dr. Benjamin Frothingham, Eliphalet Newell, Edward Goodwin, David Goodwin, Joseph Cordis, Caleb Swan, and William Calder, members of the Lodge of St. Andrew. These were held in high esteem by Lieutenant-Colonel Paul Revere (also a member of St. Andrew), who had made the famous ride of April 18. 1775, as was Hon. John Hancock (the first signer of the Declaration of Independence). The old lodge of Bunker Hill fame is King Solomon's. Its early life is in itself a rude history, as follows, to wit:

CHARTER

To All the Fraternity of Free and Accepted Masons to Whom These Presents Shall Come:

The Most Worshipful John Warren, Esq., Grand Master of Free and Accepted Masons, duly authorized and appointed, and in ample form installed, together with his Grand Warden,

(Seal) Send Greeting:

Whereas, a petition has been presented to us by Benjamin Froth-ingham, Eliphalet Newell, Edward Goodwin, Joseph Cordis, Caleb Swan and William Calder, and Ancient, Free and Accepted Masons, resident in Charlestown, in the County of Middlesex and commonwealth of Massachusetts, praying that they, with such others as may think proper to join them, may be elected and constituted a regular lodge of Free and Accepted Masons under the name, title and designation of King Solomon's Lodge. with full power to enter apprentices, pass fellow-crafts and raise Master Masons; and that their brother, Josiah Bartlett, be constituted Master; which petition appearing to us as tending to the advancement 0f Ancient Masonry, and the general good of the craft, we have unanimously agreed that the prayer thereof be granted. Know ye, therefore, that we, the Grand Master and Wardens, by virtue of the power and authority aforesaid, reposing special trust and confidence in the prudence, fidelity and skill in Masonry of our beloved brethren above named, have constituted and appointed, and by these presents do constitute and appoint them, the said Josiah Bartlett, Benjamin Frothingham, Eliphalet Newell, Edward Goodwin, David Goodwin, Joseph Cordis, Caleb Swan and William Calder, with others, a regular lodge of Free and Accepted Masons under the name, title and designation of King Solomon's Lodge, hereby giving and granting unto them and their successors full power and authority to meet and convene as Masons within the town of Charles-town aforesaid, to receive and enter apprentices, pass fellow-crafts and raise Master Masons, upon the payment of such modern compositions for the same as may hereafter be determined by said lodge. Also, to take choice of Master, Wardens and other office-bearers annually, or otherwise as they shall see cause; and we do hereby constitute and appoint our worshipful brother Josiah Bartlett, Master; and you are to receive and collect funds for the reliei" of poor and decayed brethren, their widows or children, and in general to transact all matters relating to Masonry which may appear for the good of the craft, according to the ancient usages and custom of Masons.

And we do hereby require the said constituted brethren to attend at the Grand Lodge, or quarterly communication, by themselves or their proxies (which are their Master and Wardens for the time being); and also to keep a fair and regular account of all their proceedings and lay them before the Grand Lodge when required.

And we do hereby enjoin upon our said brethren to behave themselves respectfully and obediently to their superiors in office, and not [to desert said lodge without leave from the Master and Wardens. And ppe do hereby declare the precedence of said lodge in the Grand Lodge and helsewhere to commence from the date of these presents, and require nil Ancient Masons, especially those holding of this Grand Lodge, to acknowledge and receive them and their successors as regular constituted Free and Accepted Masons, and treat them accordingly. Given under our hands and the seal of the Grand Lodge affixed at Boston, New England, this 5th day of September, 1783, and of Masonry 5783.

- Joseph Webb, G. M.

- Paul Revere, S. G. W.

- Thomas Urann, J. G. W.

- John Symmes, S. G. D.

- James Avery, J. G. D.

- William Hoskins, G. S.

- Received two guineas. John Lowell, G. Treasurer. 5th Sept., 1783.

- Received half guinea for sealing and recording. Benj. Coolidge, Secretary. * Received at the same time thirty shillings for the engrossing this charter. James Carter.

The Grand Officers had (in some capacity) served the cause of liberty during the Revolutionary War. Colonel Joseph Webb was the Grand Master during the conflict, but was with the army most of that time. (He commanded for a while at West Point during the Arnold treason) and was in close touch with General Washington throughout the entire war.

Joseph Webb Lodge of Boston is named in his honor and is a most pleasing body to visit. Colonel Paul Revere had been an artillery officer under the crown.

King Solomon's Lodge soon grew to be a mighty body. It met from its conception until a few years ago within five hundred yards from the spot where the "Grand Master of North America" fell in battle.

Dr. Josiah Bartlett, who resided on the "slope of Breed's Hill," was elected its first Master. He was an eminent man of his time. Among its earliest initiates were Dr. Oliver Holden, composer of the world famous hymn "Coronation," and Benjamin Russell (later Grand Master). Commodores John Soley and John Abbott, for whom lodges are named in Massachusetts (note: different John Abbot), were also here made Masons. Dr. Holden was Master 1797-1800. A few years ago his grave was found and is marked by a suitable stone. Dr. Holden wrote Masonic odes on the death of George Washington. Such old New England names as Adams, Snow, Holmes. Goodwin, Coombs, Worcester, Whipple, Hyde, Phipps, Hooper, Stevens, Raymond, Rogers, Bowman, Crowell, Stone, Larkin, Swan, Gregory, Dayton, Hall, Rand, Kendall, Browditch, Merriam, Page, Stearns, Tufts, Payson, Payne, Gates and Eaton are found among its earliest initiates.

In 1794 the lodge erected the "Warren" or original Breed's Hill monument. It cost about $1000 and stood on the spot where the Grand Master had fallen in battle nineteen years before. Benjamin Russell gave the land where now stands the monument. The early records of the lodge read to the effect that the battle was fought in "Brother Benjamin Russell's pasture." This was the first Masonic monument erected in this country.

The author received the Master Mason's degree in this old lodge of Charlestown on September 12, 1893, and is now a life member. The Bunker Hill Monument Association is a child of the same lodge, Brother Russell's "pasture" having been turned over to the association. The writer is also a (life) member of the Bunker Hill Monument Association.

Major-General Joseph Warren, M. D., was "thrice buried." Colonel Joseph Webb was Past Master of the Lodge of St. Andrew. George Richard Gridley (a member of St. John's Lodge of Boston), and Colonel Webb helped to fortify the hill before the battle.

A few years ago King Solomon's Lodge moved to Somerville, once a part of Charlestown, now a beautiful and residential city. Jonathan Harrington, the last survivor of the Battle of Lexington, was raised in this lodge. The membership is over 500 and its bank accounts show several Ejousand dollars in several separate funds at good interest. 1 The seal of this old lodge is of unique construction. Men of all walks nd professions in life make up its thrifty membership. The writer is honorary member of several orders and societies, and has received several degrees from institutions of learning and science, but proudest of all is he of the degrees he received in this one old lodge of the stormy days of the American past. While the mind of man remains rational, stars shine and biography has a charm in civilization, the name of King Solomon's Lodge, a little way out from the once home of the Puritans, will inspire Masonic students and the weary pilgrims to eternity. On June 17 of each year King Solomon's Lodge, through a committee of the oldest Past Masters, places a wreath of flowers on the original "Warren" monument. On each 30th of May (Decoration Day) Abraham Lincoln Camp No. 106, Sons of Veterans, U. S. A. (of which the writer is a member) decorates the "Warren" monument. A toast at fraternal and patriotic gatherings in the Revolutionary Army was to "Warren, Wooster and Montgomery." Warren was the first general to fall in battle, and on that memorable spot was erected the first Masonic monument in America. While the tide ebbs and flows twice in each twenty-four hours and "the flag of the free" floats on the "mighty deep" the rational and liberal world will look with charity, patriotism and respect upon this first Masonic monument.

Charlestown is now a part of Boston. It was settled in 1629 by the three Sprague brothers (one of whom, Ralph Sprague, was one of the senator's emigrant ancestors). These Spragues came with Governor John Winthrop to Salem. Mass., and helped to found Boston, where today Freemasonry is held in highest dignity of any city in these United States.

My gentle reader, be ye aged or in your youth, it will give you a; new lease on life to visit the land of the Puritans and Pilgrims, and while in Boston look over the iron fence on Tremont street into the Granary burial ground, where sleep such friends and Masonic brothers of Joseph Warren as Samuel Adams, John Hancock, James Otis, Paul Revere and Robert Treat Paine. Then go to Breed's Hill and see the statue of Colonel William Prescott, who took up the fight after Warren fell. Then go aloft 273 steps above the "Warren" monument to the top of the great shaft and look out upon the "mighty deep." This great shaft had its cornerstone laid by the Grand Lodge of Massachusetts Freemasons with Gus (Brother) Lafayette (32°) in attendance, wearing the apron of the ever-lamented Warren—Pro Patria.

—By Prof. Gilbert Patton Brown, Ph. D., D. C., in the Southern Masonic Journal.

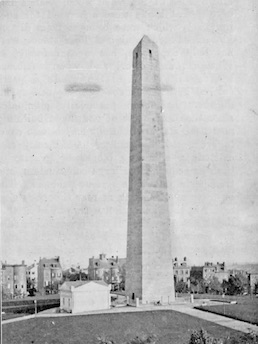

THE OBELISK ON BUNKER HILL, 1924

From New England Craftsman, Vol. XIX, No. 9, June 1924, Page 259:

The ceremony of laying the corner-stone of the Monument which commemorates the Battle of Bunker Hill, by the Grand Master of the Grand Lodge of Masons of Massachusetts. did not take place until June 17th, 1825, fifty years after the battle action. The cause of the delay may be traced to various circumstances. The deranged state of affairs at the end of the Revolutionary War was unfavorable, and the attention of the people was occupied with more pressing demands.— They were busily employed in repairing the damage caused by the war, and it was only by years of industry and economy, that they had arrived at a stage where they felt they could give consideration to such an undertaking. Soon after the second war with Great Britain in 1812, however, public interest was drawn to the subject. A meeting for devising the best mode of accomplishing the object in view, was called by patriotic citizens and met with scant attendance, but as the object became better known, more enthusiasm was manifested and in 1825 a corporation was formed under the name, the Bunker Hill Monument Association, for tlie purpose of erecting an appropriate memorial. An address was made to the public, stating its object, and soliciting subscriptions for funds. There was considerable diversity of opinion as to an appropriate form for the monument and alter a committee was appointed and officers chosen, of which Dr. John C. Warren, a relative of General Warren, was chairman, and Amos Lawrence, treasurer, it was decided to advertise for designs, which resulted in some fifty plans, of various forms and merit, being submitted, of which the obelisk and column seemed to predominate, and were consequently selected as the two motifs from *HU'h to make choice. After much discussion the committee decided on the obelisk, and a design submitted by Solomon Willard, architect of Boston, and based on a model made by Horatio Greenway, a collegian, was approved.

The design of the monument was not determined until July 5th, 1825, five weeks after the ceremony of the laying of the corner stone. The reason for having the ceremony at the time mentioned was because it was desired to have the presence of Lafayette, who was a Mason, and then visiting in the vicinity.

Daniel Webster, a Mason, delivered the oration, and it is conceded that the oration contained the clearest statement to be found anywhere, of the principles underlying the War of American Independence. President Tyler and his cabinet came from Washington for the ceremony.

It is a fact well known to the older architects who practice in New England that at the time it was proposed to build the obelisk in Charlestown to commemorate the Battle of Bunker Hill, it was difficult to find a suitable stone. Boston was surrounded by a primitive formation, and consequently wanting in all the softer kinds of stone commonly used for such purposes. Quincy granite was not then in use, except for rough work, and no successful attempt had then been made in executing moulded and ornamental work in any other kind of granite. The walls of buildings were carried up of granite in ashlar courses and generally crowned with a cornice of wood. Sandstones of different kinds were also used for such purposes, which were brought from distant places. These sand and lime stones were not only expensive, but were defective in substance and color, and when combined with granite gave to the whole a particolored and incongruous appearance. This difficulty has been practically eliminated since then and some of our finest buildings now have many mouldings and ornate carvings executed in granite. A difficulty also existed in obtaining blocks of granite of the size required for large construction, and transportation was a serious problem. The business of quarrying at that time was generally in the hands of those who had neither the means nor the skill which were necessary for carrying on a work of that magnitude in a proper manner. In work intended for monumental use, it is obvious that continuity of substance and color is an important consideration.

The plans and models were examined Inmost of those in the granite business nearby, but no proposal was offered, except by one individual whose price far exceeded the estimate. The committee thereupon decided to purchase a quarry at Quincy and do the work by the day under the superintendence of the architect, Solomon Willard, who was also the architect of the Custom House and other important public and private buildings, and the completed work showed the wisdom of this decision, as it is believed that much money was saved and the work of better quality than if done by contract.

Consideration was given for a monument with a base of 40 feet, but it was agreed that the state of the available funds would not permit of a monument of more than 30 feet and to be 220 feet in height and having a circular stairway to the top. The work was begun at the quarry November 16, 1825, and continued until January, 1829, when it was suspended for want of funds; it was re-commenced on January 17, 1834, when the ladies had raised a fund, and proceeded until November, 1835, when it was again discontinued; in November 1840, work was again started and continued until its completion in 1843, the ladies having again given aid by contributing about $30,000 which they raised through a fair.

The building of the obelisk led to the construction of the first railway in the country and the organization of the Granite Railway Company, Thomas H. Perkins, president. This railway, the motive power of which was oxen, carried the stones from the quarry in Quincy to the shore; they were then put on scows and taken to Deven's Wharf in Charlestown. A special hoisting apparatus of chains and levers for lifting the stones was designed by Almoran Holmes of Boston, a practical seaman and engineer. This apparatus was used for lifting the first 55,000 feet of granite and the remainder was hoisted by steam power. The stones averaged a little more than five tons in weight and were about 12 ft. x 2 1/2 ft. x 2 ft and contained about 55 cubic feet. About 87,000 feet of granite, weighing about 9,000 tons, was used. The total cost of the monument and land was less than one hundred thousand dollars. It could not be built at the present time for less than ten times that amount.

The centennial celebration of the battle of Bunker Hill on June 17th, 1875 was one of the grandest celebrations ever seen in this country. The city, the state and private citizens vied with each other in their efforts to make the event a glorious success. Distinguished guests were present, and man military and civic bodies from nearly all the states participated in the proceedings.

General Charles Devens delivered the oration and Mayor Cobb, Governor Gaston, Col. A. O. Andrews of South Carolina, Gen. Fitz Hugh Lee of Virginia, Gen. W. T. Sherman, Gen. A. E. Burnside and Vice-President Wilson were among the others who spoke.

Gen. Francis A. Osborne was chief marshal of the procession, which was several miles long.

THE BATTLE OF BUNKER HILL AND THE DEATH OF GENERAL WARREN

From New England Craftsman, Vol. XIX, No. 9, June 1924, Page 261:

No engagement of the American Revolutionary War possesses an interest so deep and peculiar, or produced consequences so important, as the battle of Bunker Hill; and no other engagement is involved in so much obscurity, perplexity and controversy.

It is remarkable on many accounts,— it being the first great battle of the contest,— in the astonishing resistance made by inexperienced militia against veteran troops,— in the affecting character of its prominent incidents,— in the sublimity of its spectacle, — and its influence on the politics of the day. and the fortunes of war. It proved the quality of the American soldier, drew definitely the lines of party, and established the fact of open war between the colonies anil the mother country. It was a victory with all the moral effect of victory, under the name of defeat. And yet at first it was regarded with disappointment, and even with indignation and contemporary accounts of it, whether in private or official, are more in tone of apology, or of censure, rather than of exultation. The enterprise on the whole, was pronounced rash in the conception, and discreditable in the execution, and a severe scrutiny was instituted into the conduct of those who were charged with having contributed by their backwardness, to the result. No one, for years, came forward to claim the honor of having directed it, no notice was taken of its returning anniversary; and no narrative did justice to the regiments that were engaged, or the officers that were in command. Passing events are seldom accurately estimated. The bravery, however, of those who fought, was so resolute, and their self devotion was so lofty, as at once to elicit from all quarters, the most glowing commendation, and to become the theme of the poet and the orator, and as time rolled on, its connection with the great movement of the age appeared in its true light.

Hence the battle of Hunker Hill now stands as the grand opening scene in the drama of the American Revolution. General Joseph Warren exerted great influence in the battle. Having served zealously and honorably in the incipient councils that put in motion the machinery of the Revolution, he had decided to devote his energies to promotin it in its future fields. He was accordingly elected Major General, on the 14th of June but had not received his commission on the day of the battle. Though he is understood to have opposed the measure of occupying so exposed a position as Bunker Hill, yet he avowed the intention, if it should be resolved upon, to share the peril of it. and to the affectionate remonstrance of friends, he responded: dulce et decorum eat pro patria mori.

On the 16th of June he officiated as President of the Provincial Congress, passed the night at Watertown, and though indisposed repaired on the morning of the 17th to Cambridge, where he threw himself on a bed. When he learned that the British troops would attack the redoubts thrown up on Breed's Hill by the American soldiers, he declared his headache to be gone; and after meeting with the committee of safety, armed himself and proceeded to Charlestown. A short time before the action commenced he was seen in conversation with General Putnam at the rail fence, who offered to receive his orders. General Warren declined to give any, but asked where he could be most useful. Putnam directed him to the redoubt saying, "There he would be covered." "Don't think," replied Warren, "I come to seek a place of safety! But tell me where the onset will be most furious." Putnam still pointed to the redoubt. "That is the enemy's object and if that can be held, the day is ours."

General Warren passed to the redoubt, where the men received him with enthusiastic cheers as he entered their ranks. Here he was again tendered the command, this time by General Prescott. But Warren declined it — said that he came to encourage a good cause, and gave the heartening assurance that a reinforcement of two thousand men were on their way to aid them. He mingled in the fight, behaving with great bravery and was among the last to leave the redoubt. Ha was lingering even to rashness in his retreat, and had receded but a few rods when a British bullet struck him in the forehead and he fell to the ground. On the next day visitors to the battlefield, among them Dr. Jeffries and young Winslow, afterward General Winslow, of Boston, recognized the body, and it was buried on the spot where he fell. The British loss in killed and wounded was 1054, while the American loss incurred mainly in the last hand-to-hand struggle was 449. The British had gained the victory, but the moral advantage was wholly with the Americans.

Subsequently it developed that the American generals were aware that their troops had but three rounds of ammunition remaining, and no prospect of the supply being replenished.

After the British evacuated Boston on March 17th, 1776, the sacred remains of General Warren were sought after and again identified, they were first deposited in the Granary Burying Ground, then in a tomb under St. Paul's Church, and finally in the family vault in Forest Hills Cemetery.

General Joseph Warren was born in Roxbury. Massachusetts, June 11th, 1741, graduated at Harvard College 1759, and after teaching school in Roxbury for a few years commenced the practice of medicine.

NEW ENGLAND CRAFTSMAN, 1925

From New England Craftsman, Vol. XX, No. 9, June 1925, Page 293:

hBATTLE OF BUNKER HILL

ttp://masonicgenealogy.com/MediaWiki/images/FrederickHamilton1925.jpg

Rt. Wor. Frederick W. Hamilton, Grand Secretary, Grand Lodge of Massachusetts

(Copyright 1925, by The Masonic Service Association of tlie United States. Reprinted by permission.)

The 17th of June, 1775, was one of those bright, quiet days which show the New England climate at very best. At daybreak the sleeping inhabitants of Boston and the neighboring towns were aroused by the continuous thundering of heavy guns from the upper harbor. Evidently something unusual even in those stirring times was happening. This is what it was.

Ever since the first British regiments had been sent to overawe the town of Boston some eight years before, the garrison had been increased from time to time until the British forces numbered about 10,000 men. General Gage was in command, and with him were Howe, Clinton, and Burgoyne, all familiar names in the story of the next eight years. A few weeks before, on the 19th of April, a British detachment had attempted to destroy the ammunition and supplies which the Americans had gathered at Concord. The story of what happened that day need not he retold here. Its effect, however, was of the utmost importance. The resistance of the Colonists had been solidified and strengthened. The New England militia had gathered in large numbers around Boston, and their forces were constantly increasing. Their organization, however, was crude and imperfect. Washington had been appointed to take command of the Colonial troops, but had not yet reached the neighborhood of Boston. The troops surrounding Boston were under command of General Artemus Ward. General Ward was a man of the highest character and warmest patriotism but advanced in years and of moderate military ability. From his headquarters in Cambridge he was directing the operations which amounted practically to a siege. The Americans were in sufficient force and sufficiently well posted to hold the British closely confined to the city. It was unsafe for small parties of British to venture out, and General Gage did not care to precipitate hostilities by movements in force. Each side was watching the other warily: the Americans anticipating an attempt to break out and the British fearing movements which might make their position untenable.

Under these circumstances General Ward, on June 16, sent out a working party of about 1,200 men under Colonel William Prescott to fortify Breed's Hill, in Charlestown. It does not appear to have been General Ward's intention to bring on an engagement. He appears to have had in mind only the erection of fortifications which would block an attempt of the British to gain the open country by way of the pear-shaped peninsula of Charlestown neck behind it, an exit from the city which was not fortified. Arriving on the ground, however, Prescott went beyond Breed's Hill and fortified Bunker Hill, apparently forgetting the defensive nature of the movement ordered by Ward and considering that guns mounted on Breed's Hill would be able from that point to inflict much more damage on the British in Boston and their ships in the upper harbor. This was quite true, and was the deciding element, as we shall see, in bringing on the judgment. The position, however, was much more exposed and much less easily defensible than Bunker Hill.

The first troops were accompanied by Colonel Richard Gridley, who had commanded an artillery regiment in the French wars, and had considerable training as a military engineer; almost, if not quite, the only engineer officer then in the Colonial Service. Gridley commanded the artillery and laid out the fortifications.

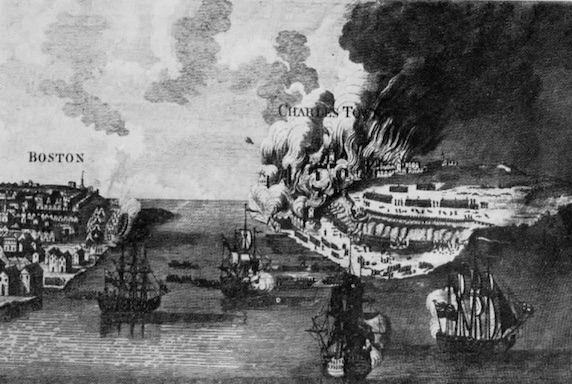

Battle of Bunker Hill,

From Painting by John Trumbull

At daybreak the Americans and their growing fortifications were seen from the British ships, which immediate1y opened fire, though with very little effect. The sound of the guns, and the news of what it signified, aroused Gage, who consulted witli his generals as to what should be done. Their decision was a very expensive blunder. It was agreed that heavy batteries on Breed's Hill would compel the evacuation of the city, exactly as it was compelled nine months later by Washington's hatteries on Dorchester Heights. There was no question that the Americans must be cleared out of that position. The position itself was a trap. The British had control of the water, and could move their troops upon it at will. Charlestown neck was narrow and could be swept by the fire of the English warships. Protected by this fire, it would have been perfectly possible to land a force which would have cut off the Americans and compelled the surrender of the entire force.

Gage was a British General of the old school, of the highest personal courage, but as arrogant and obstinate as he was brave. Concord and Lexington had taught him nothing. He did not believe that the New England militia, even behind breastworks, would stand for a moment before British regulars. He scorned to employ the obvious tactics which he would have used against an ordinary army. He probably felt that the moral effect of marching over the Americans' breastworks and sending their ill-trained defenders scuttling to the rear would be far greater than could be accomplished by scientific military manoeuver. Accordingly, at ten o'clock in the morning he issued a general order directing certain troops to assemble and march to the waterfront to be ferried across to Charlestown. The order is so drawn that it is impossible to tell at this time just what commands were indicated, or even their approximate strength. It is probable, however, that the total British force engaged, including reinforcements which were later sent over, was about 3,000 men, although some of the people of Boston reckoned it as high as 5,000. No official figures of the force engaged were ever published by the English.

The troops assembled as directed and paraded in a body through the streets of Boston. It was evidently Gage's intention to hold the ground occupied. It is an interesting side light on the military customs of the time to know that, although these men were sent out to fight, and would be separated from their base of supplies by a distance which could be traversed in two hours at the outside, they were sent out in full dress uniforms, and provided with heavy marching equipment and three days' rations. All this in the middle of a warm summer day. Such disregard of ordinary consideration for the comfort and effectiveness of soldiers on duty was characteristic of the English Army at this period, and long after. Knglish soldiers faced Hie climate of India in European uniforms and bearskin hats, while Lord Wolseley tells us that so late as 1853 he had to go into action in the steaming jungles of Burma in a close-fitting scarlet tunic with a high, tight collar.

At twelve o'clock the crossing to Charlestown began, and at three o'clock the British lines were formed for the assault and moved toward the breastworks. The British advance must have been a very beautiful spectacle. Their scarlet-clad lines moved forward with the regularity of the parade-ground, the sun reflecting in myriad points of light from the polished metal of their equipment and the rows of glittering bayonets.

Behind the American breastworks the militiamen were out of sight. Only Colonel Prescott, an experienced veteran of the French wars, walked coolly back and forth on the top of the breastworks, keeping his inexperienced and somewhat nervous men in order. The Americans had been ordered to hold their fire until the British had almost reached the breastworks and, with the exception of a few scattering shots from the nervous and impatient, the order was obeyed. When Prescott considered that the right time had come, he gave the order and a blast of fire destroyed the front ranks of the British. The first volley was followed by a rapid and continuous discharge before which in a few minutes the British broke and fled back to the shore.

In a few moments, however, discipline asserted itself, the officers reformed their men, and a second advance was made. In the meantime the town of Charlcstown had been set on fire by the British and the second assault was partly screened by clouds of smoke from the burning buildings. Again the Americans waited until the British were almost upon them, again the assailants were blasted away by the rifle fire of the defenders. British officers who had served at Fontenoy and other pitched battles on the Continent declared they had never experienced anything like it. A second time the British retreated.

Gage held a hurried consultation with his officers. The gravity of the situation was fully recognized, but British pride was not yet ready to admit defeat, and the possibility of being turned out of Boston by heavy guns which might be mounted in the American works, was again urged. Contrary to all teachings of military prudence, Gage ordered a third assault, which was delivered at five-o'clock. With extraordinary courage and tenacity the British returned to their apparently hopeless task. This time, however, the fire which received them was much less severe. They succeeded in placing some guns in position to rake the American works. The ammunition of the Americans was exhausted. Without bayonets, they had only stones and clubbed rifles with which to resist the British. Even so, they made a desperate resistance, and it was not until their defences were actually in British hands that they broke and streamed away over Charlestown neck, leaving the British in possession of the hill. It was in this last phase of the engagement that the greater part of the American losses were sustained. Among the killed and wounded at this point were Warren and Gridley and many other well-known American officers.

It is more difficult to estimate the number of Americans engaged than it is to estimate their opponents. Americans were coming and going all day, but it doubtful if more than 1,500 were actually engaged at any one time. General Gage admitted a loss of 1,054 killed and wounded. It is highly probable, however, that his loss considerably exceeded that number. General Ward's Orderly Book shows an American loss of 450, which probably substantially accurate.

In all probability the defeat of the Americans and their flight from the trap in which they had incautiously placed themselves saved them from much greater loss in the immediate future. Gage had put forth only a small part of his strength. If defeated, he would undoubtedly have renewed his attempt in a more scientific manner, and must eventually have destroyed or captured the entire American force in Charlestown.

The consequences of the battle were far-reaching. When Washington heard of it his first question was whether the Colonists stood their ground, and when informed that they did he expressed confidence in the outcome of the conflict. The British learned to have wholesome respect for the Americans, and recognized the fact that they had a war on their hands, and not a riot. The Americans throughout the Colonies were enraged at the bloodshed of this dreadful day. They too realized that they had a real war on hand and not an armed protest. After Bunker Hill it became increasingly clear that it was useless to hope any longer for an accommodation with the British Government, and that the issue of independence or complete subjugation was clearly drawn. Up to Bunker Hill most Americans still hoped to secure their rights under the British flag. After Bunker Hill that hope faded to nothingness.

Considering this momentous event, it is in the highest degree important that we of one hundred and fifty years later should remember exactly what it was for which the Americans fought. The animating spirit of the Revolution was not the assertion of nationality or a desire to be independent for independence's sake. Up to the day of Bunker Hill, and beyond it, that great majority of the American Colonists who were of English blood were, in heart and in mind, thoroughly devoted to England. They were nationalists to the core, but their nationalism was English nationalism. Their most cherished spiritual and intellectual possession was that heritage of rights and liberties and political ideals, traditions, and aspirations which had developed through the centuries on English soil and under the English flag. These had been flouted and invaded, not by the English people, but by the English Government.

The English Government had fallen into the hands of a race of petty German sovereigns. On the death of Queen Anne the Crown had passed to George, the Elector of Hanover, known as George I of England, who was succeeded in direct descent bv George II, and George III. who was King at the time of which I write. George I and George II were thoroughly German. George III — "Farmer George," as he liked to be called — prided himself on being an English gentleman. It is true that he was born in England, but all his inheritance, instincts, and traditions were German. The Hanoverian kings were never English in heart. Their political inheritance was German absolutism. They were impatient of English ideas, ignorant of English traditions, and unsympathetic witli English ideals. George III did indeed govern England through the ordinary machinery of the two Houses of Parliament and a Ministry, but at this time he dominated Parliament in both Houses through a group known as "The King's Friends." rhrough this domination of Parliament he was doing his best to substitute Ger-uan absolutism for English freedom. The treatment accorded the Colonies by the King and his Ministers was a part of this general plan. The age-long liberties of :he English people were in danger wher-sver the English flag flew, and it was for :hese liberties that the Americans took up arms.

The Americans had no means of breaking this un-English control of the government except by throwing off their allegiance to the mother country. The ordinary methods of political opposition or if resistance at the polls were not open to them. They were placed in the curious attitude of making war against the English Government in order to preserve or themselves the English political system. The success of the struggle for independence was the death blow of the personal government of the Hanoverian kings. Shortly after the end of the Revolutionary War, another revolution took place in England itself. This revolution is often overlooked because in its course not a shot was fired nor a life lost, but when it was over the principles of English liberty were reassured. "The King's Friends" had ceased to be a political power, and the way was clear for the development of the English Constitution and the government organized under if along its traditional lines. The Battle of Bunker Hill was as significant in the history of the English people as it was in the history of the Americans.

Statue of Warren on Bunker Hill

The Battle of Bunker Hill, considered as the crucial incident in this great struggle, has a particular interest to Freemasonry. Its most obvious interest lies in the participation in it of prominent members of the Fraternity and the tragic death of the most conspicuous of them. Joseph Warren was Provincial Grand Master for North America under a Warrant from the Grand Master of Scotland. In that capacity he had shown the zeal and powers of leadership which distinguished him in other fields. He had been Provincial Grand Master only since 1769, but in that period had shown intense activity, and had not only greatly increased the number of Lodges under his charge, but had impressed them deeply with the vigor of his wise personality, and the earnestness of his Masonic convictions. As a citizen he had early identified himself with the patriotic party. Wise in counsel and energetic in action, he had taken a high position in that goup of leaders who will never be forgotten so long as American history is read.

Joseph Warren Volunteering His Services to Gen. Israel Putnam

Before the Battle of Bunker Hill

He had been chosen President of the Massachusetts Congress, as the Legislature was then called, and held a commission as Major General. Unfortunately for the cause which was so dear to him, his ardent temperament and ear-Best desire to be of personal use led him to forget the great responsibilities of the two positions which he held. He did not stop to think that a life charged with such important duties and responsibilities was too valuable to his country to be risked on the battle-field. Waiving his rank, he rode to the battle-field and offered his services to Putnam, who shared the command with Prcscott, and asked to be put where he could be of the greatest use. He fought bravely in the ranks, and did his best to help the retreating troops get away with as little harm as possible, but was killed in the very last moments of the fight. Undoubtedly the death of so distinguished a leader and the example of his personal heroism was of immense influence at the time, and has made a lasting appeal to the patriotism and to the courage of generations. And yet one cannot help wishing that abilities and character so transcendant might have been spared for the service of his country.

Colonel Gridley, the engineer and artillery officer, who was wounded in the fight, was District Grand Master of the other Provincial Grand Lodge which was operating under the Warrant issued by the Grand Master of England in 1733. Putnam, who commanded the Connecticut contingent, and John Stark, who commanded the New Hampshire men, were both active and well-known members of the Fraternity. Others there were who shared their affiliations, but the time possible for the preparation of this article has not permitted the interesting task of tracing out these personal details.

Behind the personalities of the Masons who took a leading part on this historic day lie the principles of Freemasonry which inspired these men and many others to take the position they did when the great issues of the time were defined. We must remember, what we sometimes forget, that modern Freemasonry is distinctly an English institution. While ancient Freemasonry struck its roots far into a remote past and distant lands, the direct connection with these ancient Craftsmen and their thought and work can be traced only in England and Scotland. It was there that the Grand Lodges of our modern type were formed. It was there and in the preceding generations that Operative Masonry became slowly developed into Speculative Masonry. It was from there that Masonry spread to the English Colonies, and also to the Continent of Europe. Masonry, in other words, has grown up on English soil and in the English soul. Its fundamental principles of reverence for the Grand Architect of the Universe, truth, honor, and fair dealing between men, broad tolerance of individual opinion, and equality before the law, were at the same time the fundamentals of the best English political and social thinking. The best in English life expressed itself in Freemasonry, and nowhere outside of England could Freemasonry have found scope and support for its development. When Freemasonry came to America it made its appeal to the best hearts and minds in the community. Here, as elsewhere, the Masons, being a carefully selected and self-perpetuating group, were in advance of the development of the mass of their fellow-citizens.

Freemasonry, as an organization, was true to its immemorial principles of barring from the lodge-room all discussions of religion or politics, and refraining absolutely from any participation as an organization in any political movements. Whig and Tory sat side by side in Masonic Lodges. Boston patriots and soldiers from the English regiments quartered in Boston joined under the Charter of Saint Andrew's Lodge to form Saint Andrew's Royal Arch Chapter. Freemasonry did not desert its purpose of furnishing a common ground upon which honest men of all shades of opinion might meet on terms of mutual respect.

But Freemasons inevitably assumed positions of leadership on the side of the liberty of the citizen and the freedom of the individual. The same considerations which carried leading Freemasons of that day into the forefront of public life send the same call of duty to the Freemasons of today. The same devotion to high principle which made these men leaders and impressed their thought and personality so deeply on the history of that time will produce the same results today. It is not the cry of an alarmist to say that, our institutions are in danger. All good institutions are always in danger. The forces of selfishness, greed, ambition, treachery, ignorance, and superstition are part of human nature; they always have threatened the progress of the human race, and they alwav-s will threaten it in any future of which we need to take account. The same clear-sighted courage and indomitable energy which saved the day one hundred and fifty years ago are called for today. The present writer believes that the call will not fall on deaf ears, and that once again, as so many times in the past, the forces of righteousness will conquer.

Lord Howe and the American Commissioners

In Conference, 1776

NEW ENGLAND CRAFTSMAN, 1932

From New England Craftsman, Vol. XXVII, No. 6, February 1932, Page 158:

Erected A.D. 1794 by King Solomon's Lodge of Freemasons, Constituted at Charlestown. 1783, in Memory of Major General Joseph Warren and His Associates who were slain on the memorable spit on June 17, 1775.

THE FIRST SOLDIER'S MONUMENT IN THE UNITED STATES

By DeBert Wakelee, Past Master, King Solomon's Lodge

In telling the story of this monument let me take you back to the days just after the close of the Revolutionary War to a room in Richard Trumbull's house in Charlestown on the day of August 20, 1783. There were gathered in that room eight men of Charlestown, all Masons. Each man had been active in some capacity in the long struggle for liberty which had just ended. They were Benjamin Frothingham. Eliphalet Newell, Edward Goodwin, David Goodwin, Josiah Bartlett, Joseph Cordis. Caleb Swan and William Calder. and they voted to present a memorial to the grand lodge asking for a charter for a Masonic lodge in Charlestown to be known as King Solomon's Lodge, and the same was duly presented to the grand lodge, and on September 5. 1783. this prayer being granted, a charter was issued and the lodge has been in continual operation since that date, with an unbroken line of records. At the Battle of Bunker Hill, Major General Joseph Warren (who was fighting as a private) was killed June 17. 1775. General Warren was Grand Master of the Massachusetts Grand Lodge, and as such his memory was dear to all members of the Craft, so that on November 11, 1794, at a meeting of King Solomon's Lodge (now of Somerville) it was voted that a committee be appointed to erect a monument in mean ory of our late brother, the Most Worshipful Joseph Warren. This monument was to be erected in the name of King Solomon's Lodge, and to stand in Mr. Russell's pasture (providing the land could be procured). The committee was authorized to draw upm the treasurer to defray the expenses of the same, and when the monument was finished, they report their doings to the lodge.

This committee: Bro. Josiah Bartlett, Bro. John Soley, Bro. Eliphalet Newell, Bro. William Calder, Bro. David Stearns, attended to their work most promptly, and on December 3, 1794, reported to the lodge as follows: That they first waited upon the Hon. James Russell for his permission to proceed and that he generously offered a deed of as much land as might be necessary for the purpose. They then proceeded to erect a "Tuscan Pillar" eighteen (18) feet in height, placed upon a platform eight (8) feet high. eight feet square and fenced around to protect it. On the top of the pillar was placed a gilt urn with the initials and age of General Warren enclosed in the square and compass. On the southwest side of the pedestal the following inscription appeared on a slate tablet:

"None but they who set a just value upon the blessings of Liberty are worthy to enjoy her." "In vain we toiled; in vain we fought; we bled in vain, if you our offspring want for valor to repel the assaults of her invaders." Charlestown settled 1628, hurnt 1775, rebuilt 1770. The enclosed land given by Hon. James Russell."